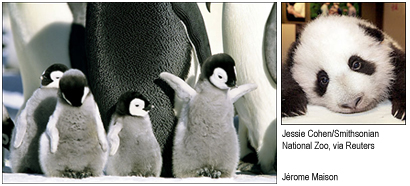

Lots of things have been really cute lately. There is a baby panda at the National Zoo and the world has gone ga-ga over him. You can watch him all day long on the pandacam if you want – he was just sleeping when I checked. Jessie is in total love and actually has a giant stuffed panda in her office now (courtesey of Animal Planet). It sits in one of her chairs and keeps her company. A few weeks back, Chris posted a link to this incredibly cute website called Cute Overload. Be careful, you’ll start hugging and mushing the screen. Of course my dog Bingham looks like a fluffy Ewok and is way too cute to get angry at, even when he’s unfurled an entire toilet paper roll and is caught in the act of happily muching away. Then there are these pics below of super cute baby penguins and the aforementioned panda cub:

So, it was great timing to see in today’s NY Times Science section article about the science of cute. Here’s a snipit: “Scientists who study the evolution of visual signaling have identified a wide and still expanding assortment of features and behaviors that make something look cute: bright forward-facing eyes set low on a big round face, a pair of big round ears, floppy limbs and a side-to-side, teeter-totter gait, among many others.

The article is actually fantastic, and some parts of it are incredibly funny, like how it says that humans find anything deemed needy and pathetic very cute because we ourselves are pathetic and so reliant on others when born.

Feel free to go to the Times article itself (and see some uber-cute pics) or if that isn’t available, read the entire article after the jump. Its long (over 2000 words) but totally worth it.

January 3, 2006

The Cute Factor

By Natalie Angier

WASHINGTON, Jan. 2 – If the mere sight of Tai Shan, the roly-poly, goofily gamboling masked bandit of a panda cub now on view at the National Zoo isn’t enough to make you melt, then maybe the crush of his human onlookers, the furious flashing of their cameras and the heated gasps of their mass rapture will do the trick.

“Omigosh, look at him! He is too cute!”

“How adorable! I wish I could just reach in there and give him a big squeeze!”

“He’s so fuzzy! I’ve never seen anything so cute in my life!”

A guard’s sonorous voice rises above the burble. “OK, folks, five oohs and aahs per person, then it’s time to let someone else step up front.”

The 6-month-old, 25-pound Tai Shan – whose name is pronounced tie-SHON and means, for no obvious reason, “peaceful mountain” – is the first surviving giant panda cub ever born at the Smithsonian’s zoo. And though the zoo’s adult pandas have long been among Washington’s top tourist attractions, the public debut of the baby in December has unleashed an almost bestial frenzy here. Some 13,000 timed tickets to see the cub were snapped up within two hours of being released, and almost immediately began trading on eBay for up to $200 a pair.

Panda mania is not the only reason that 2005 proved an exceptionally cute year. Last summer, a movie about another black-and-white charmer, the emperor penguin, became one of the highest-grossing documentaries of all time. Sales of petite, willfully cute cars like the Toyota Prius and the Mini Cooper soared, while those of noncute sport utility vehicles tanked.

Women’s fashions opted for the cute over the sensible or glamorous, with low-slung slacks and skirts and abbreviated blouses contriving to present a customer’s midriff as an adorable preschool bulge. Even the too big could be too cute. King Kong’s newly reissued face has a squashed baby-doll appeal, and his passion for Naomi Watts ultimately feels like a serious case of puppy love – hopeless, heartbreaking, cute.

Scientists who study the evolution of visual signaling have identified a wide and still expanding assortment of features and behaviors that make something look cute: bright forward-facing eyes set low on a big round face, a pair of big round ears, floppy limbs and a side-to-side, teeter-totter gait, among many others.

Cute cues are those that indicate extreme youth, vulnerability, harmlessness and need, scientists say, and attending to them closely makes good Darwinian sense. As a species whose youngest members are so pathetically helpless they can’t lift their heads to suckle without adult supervision, human beings must be wired to respond quickly and gamely to any and all signs of infantile desire.

The human cuteness detector is set at such a low bar, researchers said, that it sweeps in and deems cute practically anything remotely resembling a human baby or a part thereof, and so ends up including the young of virtually every mammalian species, fuzzy-headed birds like Japanese cranes, woolly bear caterpillars, a bobbing balloon, a big round rock stacked on a smaller rock, a colon, a hyphen and a close parenthesis typed in succession.

The greater the number of cute cues that an animal or object happens to possess, or the more exaggerated the signals may be, the louder and more italicized are the squeals provoked.

Cuteness is distinct from beauty, researchers say, emphasizing rounded over sculptured, soft over refined, clumsy over quick. Beauty attracts admiration and demands a pedestal; cuteness attracts affection and demands a lap. Beauty is rare and brutal, despoiled by a single pimple. Cuteness is commonplace and generous, content on occasion to cosegregate with homeliness.

Observing that many Floridians have an enormous affection for the manatee, which looks like an overfertilized potato with a sock puppet’s face, Roger L. Reep of the University of Florida said it shone by grace of contrast. “People live hectic lives, and they may be feeling overwhelmed, but then they watch this soft and slow-moving animal, this gentle giant, and they see it turn on its back to get its belly scratched,” said Dr. Reep, author with Robert K. Bonde of “The Florida Manatee: Biology and Conservation.”

“That’s very endearing,” said Dr. Reep. “So even though a manatee is 3 times your size and 20 times your weight, you want to get into the water beside it.”

Even as they say a cute tooth has rational roots, scientists admit they are just beginning to map its subtleties and source. New studies suggest that cute images stimulate the same pleasure centers of the brain aroused by sex, a good meal or psychoactive drugs like cocaine, which could explain why everybody in the panda house wore a big grin.

At the same time, said Denis Dutton, a philosopher of art at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, the rapidity and promiscuity of the cute response makes the impulse suspect, readily overridden by the angry sense that one is being exploited or deceived.

“Cute cuts through all layers of meaning and says, Let’s not worry about complexities, just love me,” said Dr. Dutton, who is writing a book about Darwinian aesthetics. “That’s where the sense of cheapness can come from, and the feeling of being manipulated or taken for a sucker that leads many to reject cuteness as low or shallow.”

Quick and cheap make cute appealing to those who want to catch the eye and please the crowd. Advertisers and product designers are forever toying with cute cues to lend their merchandise instant appeal, mixing and monkeying with the vocabulary of cute to keep the message fresh and fetching.

That market-driven exercise in cultural evolution can yield bizarre if endearing results, like the blatantly ugly Cabbage Patch dolls, Furbies, the figgy face of E.T., the froggy one of Yoda. As though the original Volkswagen Beetle wasn’t considered cute enough, the updated edition was made rounder and shinier still.

“The new Beetle looks like a smiley face,” said Miles Orvell, professor of American studies at Temple University in Philadelphia. “By this point its origins in Hitler’s regime, and its intended resemblance to a German helmet, is totally forgotten.”

Whatever needs pitching, cute can help. A recent study at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center at the University of Michigan showed that high school students were far more likely to believe antismoking messages accompanied by cute cartoon characters like a penguin in a red jacket or a smirking polar bear than when the warnings were delivered unadorned.

“It made a huge difference,” said Sonia A. Duffy, the lead author of the report, which was published in The Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. “The kids expressed more confidence in the cartoons than in the warnings themselves.”

Primal and widespread though the taste for cute may be, researchers say it varies in strength and significance across cultures and eras. They compare the cute response to the love of sugar: everybody has sweetness receptors on the tongue, but some people, and some countries, eat a lot more candy than others.

Experts point out that the cuteness craze is particularly acute in Japan, where it goes by the name “kawaii” and has infiltrated the most masculine of redoubts. Truck drivers display Hello Kitty-style figurines on their dashboards. The police enliven safety billboards and wanted posters with two perky mouselike mascots, Pipo kun and Pipo chan.

Behind the kawaii phenomenon, according to Brian J. McVeigh, a scholar of East Asian studies at the University of Arizona, is the strongly hierarchical nature of Japanese culture. “Cuteness is used to soften up the vertical society,” he said, “to soften power relations and present authority without being threatening.”

In this country, the use of cute imagery is geared less toward blurring the line of command than toward celebrating America’s favorite demographic: the young. Dr. Orvell traces contemporary cute chic to the 1960’s, with its celebration of a perennial childhood, a refusal to dress in adult clothes, an inversion of adult values, a love of bright colors and bloopy, cartoony patterns, the Lava Lamp.

Today, it’s not enough for a company to use cute graphics in its advertisements. It must have a really cute name as well. “Companies like Google and Yahoo leave no question in your mind about the youthfulness of their founders,” said Dr. Orvell.

Madison Avenue may adapt its strategies for maximal tweaking of our inherent baby radar, but babies themselves, evolutionary scientists say, did not really evolve to be cute. Instead, most of their salient qualities stem from the demands of human anatomy and the human brain, and became appealing to a potential caretaker’s eye only because infants wouldn’t survive otherwise.

Human babies have unusually large heads because humans have unusually large brains. Their heads are round because their brains continue to grow throughout the first months of life, and the plates of the skull stay flexible and unfused to accommodate the development. Baby eyes and ears are situated comparatively far down the face and skull, and only later migrate upward in proportion to the development of bones in the cheek and jaw areas.

Baby eyes are also notably forward-facing, the binocular vision a likely legacy of our tree-dwelling ancestry, and all our favorite Disney characters also sport forward-facing eyes, including the ducks and mice, species that in reality have eyes on the sides of their heads.

The cartilage tissue in an infant’s nose is comparatively soft and undeveloped, which is why most babies have button noses. Baby skin sits relatively loose on the body, rather than being taut, the better to stretch for growth spurts to come, said Paul H. Morris, an evolutionary scientist at the University of Portsmouth in England; that lax packaging accentuates the overall roundness of form.

Baby movements are notably clumsy, an amusing combination of jerky and delayed, because learning to coordinate the body’s many bilateral sets of large and fine muscle groups requires years of practice. On starting to walk, toddlers struggle continuously to balance themselves between left foot and right, and so the toddler gait consists as much of lateral movement as of any forward momentum.

Researchers who study animals beloved by the public appreciate the human impulse to nurture anything even remotely babylike, though they are at times taken aback by people’s efforts to identify with their preferred species.

Take penguins as an example. Some people are so wild for the creatures, said Michel Gauthier-Clerc, a penguin researcher in Arles, France, “they think penguins are mammals and not birds.” They love the penguin’s upright posture, its funny little tuxedo, the way it waddles as it walks. How like a child playing dress-up!

Endearing as it is, Dr. Gauthier-Clerc explained that the apparent awkwardness of the penguin’s march had nothing to do with clumsiness or uncertain balance. Instead, he said, penguins waddle to save energy. A side-to-side walk burns fewer calories than a straightforward stride, and for birds that fast for months and live in a frigid climate, every calorie counts.

As for the penguin’s maestro garb, the white front and black jacket suits its aquatic way of life. While submerged in water, the penguin’s dark backside is difficult to see from above, camouflaging the penguin from potential predators of air or land. The white chest, by contrast, obscures it from below, protecting it against carnivores and allowing it to better sneak up on fish prey.

The giant panda offers another case study in accidental cuteness. Although it is a member of the bear family, a highly carnivorous clan, the giant panda specializes in eating bamboo.

As it happens, many of the adaptations that allow it to get by on such a tough diet contribute to the panda’s cute form, even in adulthood. Inside the bear’s large, rounded head, said Lisa Stevens, assistant panda curator at the National Zoo, are the highly developed jaw muscles and the set of broad, grinding molars it needs to crush its way through some 40 pounds of fibrous bamboo plant a day.

When it sits up against a tree and starts picking apart a bamboo stalk with its distinguishing pseudo-thumb, a panda looks like nothing so much like Huckleberry Finn shucking corn. Yet the humanesque posture and paws again are adaptations to its menu. The bear must have its “hands” free and able to shred the bamboo leaves from their stalks.

The panda’s distinctive markings further add to its appeal: the black patches around the eyes make them seem winsomely low on its face, while the black ears pop out cutely against the white fur of its temples.

As with the penguin’s tuxedo, the panda’s two-toned coat very likely serves a twofold purpose. On the one hand, it helps a feeding bear blend peacefully into the dappled backdrop of bamboo. On the other, the sharp contrast between light and dark may serve as a social signal, helping the solitary bears locate each other when the time has come to find the perfect, too-cute mate.